Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is an application-layer protocol for transmitting hypermedia documents, such as HTML

- HTTP is one of the essential technologies used by the World Wide Web (WWW)

The main features of HTTP are:

Uses Client-Server model: The client asks the server for resources, and the server replies

Based on a request and a response

HTTP is simple: human-readable text protocol

HTTP is extendable: easy to implement new features (by adding headers)

HTTP is a stateless protocol:

- Meaning that the server does not keep any data (state) between two requests

- HTTP protocol itself does not store state

- Not session less, HTTP Cookies allow the use of stateful sessions

Transport protocol agnostic: HTTP is often based on TCP/IP layer it can be used on any reliable transport layer

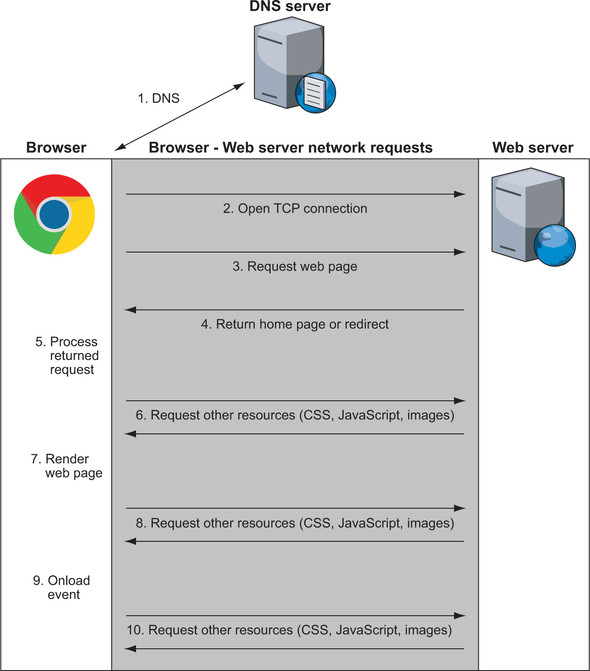

What happens when you browse the web?

Short version:

Client asks DNS Recursive Resolver to lookup a hostname (

stanford.edu)DNS Recursive Resolver sends DNS query to Root Nameserver

- Root Nameserver responds with IP address of TLD Nameserver (

.edu, etc.)

- Root Nameserver responds with IP address of TLD Nameserver (

DNS Recursive Resolver sends DNS query to TLD Nameserver

DNS Recursive Resolver sends DNS query to Domain Nameserver

- Domain Nameserver is authoritative, sp replies with server IP address

DNS Recursive Resolver finally responds to Client, sending server IP address (

171.67.215.200)

Detailed version:

The browser requests for the actual address of www.google.com from a Domain Name System (DNS) server

- DNS might perform multiple steps. Hence it is called a recursive resolver

- DNS returns an IP address

- This IP address can be in an IPv4 or the newer IPv6

The browser asks your computer to open a Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) connection over IP to this address on the standard web port (port

80) or over the standard secure web port (port443)IP is used to direct traffic through the internet, but TCP adds stability and retransmissions to make the connection reliable

TCP/IP together, they form the backbone of much of the internet

When the browser connects to the web-server, it can ask for the website. This step is where HTTP comes in, and the web browser uses HTTP to ask the Google server for the Google home page

The actual full URL includes the port and would be http://www.google.com:80, but if standard ports are being used (

80for HTTP and443for HTTPS), the browser hides the portIf non-standard ports are being used, the port is shown. Some systems, particularly in development environments, use port

8080for HTTP or8443for HTTPS, for example

The Google server responds with whatever URL you asked for. Typically, what gets sent back from the initial page is the text that makes up the web page in HTML format

Instead of an HTML page, the response may be an instruction to go to a different location. Google, for example, runs only on HTTPS, so if you go to http://www.google.com, the response is a special HTTP instruction (usually, a

301or302response code) that redirects to a new location at https://www.google.comSimilarly, if something goes wrong, you get back an HTTP response code, the best-known of which is the

404Not Found response code

The web browser processes the returned request. Assuming that the returned response is HTML, the browser starts to parse the HTML code and builds in memory the Document Object Model (DOM), which is an internal representation of the page

The web browser requests any additional resources it needs. Each of these resources is requested similarly, following steps 1-6, and yes, that includes this step because those resources may, in turn, request other resources. The average website isn't as lean as Google and needs 75 resources, often from many domains, so steps 1-6 must be repeated for all of them. This situation is one of the key things that makes web browsing slow and one of the key reasons for HTTP/2, the primary purpose of which is to make requesting these additional resources more efficient

The browser starts to render the page on-screen when it has enough critical resources. Choosing when to begin rendering the page is challenging and more complex than it sounds. If the web browser waits until all resources are downloaded, it will take a long time to show web pages, and the web will be an even slower, more frustrating place. But if the web browser starts to render the page too soon, you end up with the page jumping around as more content downloads, which is irritating if you're in the middle of reading an article when the page jumps down. A firm understanding of the technologies that make up the web-especially HTTP and HTML/CSS/JavaScript can help website owners reduce these annoying jumps while pages are being loaded, but far too many sites don't optimize their pages effectively to prevent these jumps

After the initial display of the page, the web browser continues, in the background, to download other resources that the page needs and update the page as it processes them. These resources include non-critical items such as images and advertising tracking scripts. As a result, you often see a web page displayed initially without images (especially on slower connections), with images being filled in as more of them are downloaded

When the page is fully loaded, the browser stops the loading icon (a spinning icon on or near the address bar for most browsers) and fires the

onloadJavaScript event, which JavaScript code may use as a sign that the page is ready to perform specific actionsThe page is fully loaded at this point, but the browser hasn't stopped sending out requests. We're long past the days when a web page was a page of static information. Many web pages are now feature-rich applications that continually communicate with various servers on the internet to send or load additional content. This content may be user-initiated actions, such as when you type requests in the search bar on Google's home page and instantly see search suggestions without having to click the Search button, or it may be application-driven actions, such as your Facebook or Twitter feed's automatically updating without your having to click a refresh button. These actions often happen in the background and are invisible to you, especially advertising and analytics scripts that track your actions on the site to report analytics to website owners and/or advertising networks

HTTP Versions

The HTTP Request and Response syntax have been updated in each version

HTTP/0.9

The first published specification for HTTP was version 0.9, issued in 1991

Connection is made over TCP/IP or a similar connection-oriented service

Optional port or 80 if no port is provided (allocated to HTTP by Jon Postel/ISI-24-Jan-92)

A single line of ASCII text should be sent, consisting of GET, the document address (with no spaces), and a carriage return and line feed (the carriage return being optional)

Response is a message in HTML format ("a byte stream of ASCII characters")

The connection is closed after each response is received

Hard to distinguish an error response from a satisfactory response

Server doesn't store any information about the request, hence it is stateless

The only possible command in HTTP/0.9:

GET /page.html↵Where:

GETis an HTTP method/page.htmlis the resource that we need

NOTE

There is no concept of headers in HTTP/0.9 or any other media, such as images

HTTP/1.0

The HTTP/1.0 RFC is not a formal specification and was published in 1996

More request methods: HEAD and POST were added to the previously defined GET

Addition of an optional HTTP version number for all messages. HTTP/0.9 is assumed by default to aid in backward compatibility

HTTP headers, which could be sent with both the request and the response to provide more information about the resource being requested and the response being sent

A 3-digit response code indicating (for example) whether the response was successful. This code also enabled redirect requests, conditional requests, and error status (404)

GET can send data in the form of query parameters that are specified at the end of a URL, after the ? character e.g.

https://www.google.com/?q=search+string

Request Syntax

With headers:

GET /page.html HTTP/1.0↵

Header1: Value1↵

Header2: Value2↵

↵And without headers:

GET /page.html HTTP/1.0↵

↵Here we can see some changes to the HTTP/1.0 GET request as compared to HTTP/0.9:

- The first line now contains an optional HTTP version section

- Then an optional HTTP header section followed by two return characters (

↵)

Useful HTTP Request Headers

Host: The domain name of the server (e.g. example.com)User-Agent: The name of your browser and operating systemReferer: The webpage which led you to this page (misspelled)Cookie: The cookie server gave you earlier; keeps you logged inCache-Control: Specifies if you want a cached response or notIf-Modified-Since: Only send resource if it changed recentlyConnection: Control TCP socket (e.g.keep-aliveorclose)Accept: Which type of content we want (e.g.text/html)Accept-Encoding: Encoding algorithms we understand (e.g.gzip)Accept-Language: What language we want (e.g.es)

Example:

curl https://twitter.com --header "Accept-Language: kn" --silent | grep JavaScriptResponse Syntax

A typical response from a HTTP/1.0 server:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Date: Sun, 27 Sep 2020 13:30:24 GMT

Content-Type: text/html

Server: Apache

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

etc...- The first line consists of an HTTP version (HTTP/1.0), a 3-digit HTTP status code (200), and a text description of that status code (OK)

Useful HTTP Response Headers

Date: When response was sentLast-Modified: When content was last modifiedCache-Control: Specifies whether to cache response or notExpires: Discard response from cache after this dateVary: List of headers which affect response; used by cacheSet-Cookie: Set a cookie on the clientLocation: URL to redirect the client to (used with 3xx responses)Connection: Control TCP socket (e.g.keep-aliveorclose)Content-Type: Type of content in response (e.g.text/html)Content-Encoding: Encoding of the response (e.g.gzip)Content-Language: Language of the response (e.g.kn)Content-Length: Length of the response in bytes

Example:

curl https://twitter.com --header "Accept-Language: kn" --silent | grep JavaScriptHTTP/1.1

The first HTTP/1.1 specification was published in January 1997, updated Specification in June 1999, and then enhanced for a third time in June 2014

Host

Host is a Mandatory header. The URL provided with the first line of an HTTP request isn't an absolute URL but a relative URL

Nowadays, many web servers host several sites on the same server (a situation is known as virtual hosting), so it's important to tell the server which site you want as well as which relative URL you want on that site

The host header was implemented to include the full absolute URL

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.google.comConversation over the HTTP host header

WARNING

GET / HTTP/1.1The above request is not according to the HTTP/1.1 specification, this request should be rejected by the server (with a 400 response code). Most of the web servers are more forgiving than they should be and have a default host that is returned for such requests

Connection

The connection between the server and the client is closed after each request. This created unnecessary delays while requesting multiple resources

Hence, the new Connection HTTP header with the value Keep-Alive was added, so that the client can ask the server to keep the connection open for additional requests

GET /page.html HTTP/1.0

Connection: Keep-Alive- If the server supports persistent connections, it includes a

Connection: Keep-Aliveheader in the response:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Date: Sun, 25 Jun 2017 13:30:24 GMT

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 12345

Server: Apache

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

etc...It is difficult to know when the response is completed and when the client sends another request. To overcome this,

Content-LengthHTTP header is used to define the length of the response body, and when the entire body is received, the client is free to send another requestHTTP/1.1 sets

Connection: Keep-Aliveby default, hence no need of including it in the header (some clients and servers include this)If the server did want to close the connection, it had to explicitly include a

Connection: closeHTTP header in the response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 25 Jun 2017 13:30:24 GMT

Connection: close

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Server: Apache

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

etc...

Connection closed by foreign host.| HTTP Version | Connection Header | Connection |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP/1.0 | Not Included | Closed |

| HTTP/1.0 | Included | Kept open |

| HTTP/1.1 | Both | Kept open |

NOTE

Connection header is supported by many HTTP/1.0 servers, even though it wasn't included in the HTTP/1.0 specification

HTTP/1.1 added the concept of pipelining, it is possible to send several requests over the same persistent connection and get the responses back in order. If a web browser is processing an HTML document, for example, and sees that it needs a CSS file and a JavaScript file, it should be able to send the requests for these files together and get the responses back in order rather than waiting for the first response before sending the second request

GET /style.css HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

GET /script.js HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 25 Jun 2017 13:30:24 GMT

Content-Type: text/css; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 1234

Server: Apache

.style { ... }

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 25 Jun 2017 13:30:25 GMT

Content-Type: application/x-javascript; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 5678

Server: Apache

Function(){ ... }IMPORTANT

Support for pipelining in both clients (browsers) and servers is poor

So, HTTP/1.1 is still fundamentally a request-and-response protocol for most implementations. While that one request is being handled, the HTTP connection is blocked from being used for other requests

Other New Features

- New methods are

PUT,OPTIONS, and the less-usedCONNECT,TRACE, andDELETE - Better caching methods. These methods allowed the server to instruct the client to store the resource (such as a CSS file) in the browser's cache so it could be reused later if required. The Cache-Control HTTP header introduced in HTTP/1.1 had more options than the Expires header from HTTP/1.0

- HTTP cookies to allow HTTP sessions and move from the stateless protocol

- The introduction of character sets (as shown in some examples in this chapter) and language in HTTP responses

- Proxy support

- Authentication

- New status codes

- Trailing headers

HTTP Response Status Codes

Categories of Status Codes:

1xx: Informational ("Hold on")2xx: Success ("Here you go")3xx: Redirection ("Go away")4xx: Client error ("You messed up")5xx: Server error ("I messed up")

- The status codes and descriptions are not present in HTTP/0.9

Here are some of the response codes (List of all status codes):

| Category | Value | Description (Status Message) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

1xx (informational) | 100 | Continue | Everything so far is OK and that the client should continue with the request or ignore it if it is already finished |

101 | Switching Protocols | The client has asked the server to change protocols and the server has agreed to do so | |

102 | Processing | The server has received and is processing the request, but that it does not have a final response yet | |

103 | Early Hints | Used to return some response headers before final HTTP message | |

2xx (successful) | 200 | OK | The standard response code for a successful request |

201 | Created | Should be returned for a POST request | |

202 | Accepted | The request is being processed but hasn't completed processing yet | |

204 | No content | The request has been accepted and processed, but there's no BODY response to send back | |

206 | Partial Content | The request has succeeded and the body contains the requested ranges of data, as described in the Range header of the request (succeeded) | |

3xx (redirection) | 300 | Multiple choices | This code isn't used directly. It explains that the 3xx category implies that the resource is available at one (or more) locations, and the exact response provides more details on where it is |

301 | Moved permanently | The resource has a new parament URL. The Location HTTP response header should provide the new URL of the resource | |

302 | Moved temporarily | The resource temporarily resides at a different URL. The Location HTTP response header should provide the new URL of the resource | |

304 | Not modified | The resource has not been modified since last cached. This code is used for conditional responses in which the BODY doesn't need to be sent again | |

4xx (client error) | 400 | Bad request | The request couldn't be understood and should be changed before resending |

401 | Unauthorized | You're not authenticated | |

403 | Forbidden | You're authenticated, but your credentials don't have access | |

404 | Not found | Indicates that the server cannot find the requested resource | |

429 | Too Many Requests | Indicates the user has sent too many requests in a given amount of time ("rate limiting") | |

451 | Unavailable For Legal Reasons | Indicates that the user requested a resource that is not available due to legal reasons, such as a web page for which a legal action has been issued | |

5xx (server error) | 500 | Internal server error | The request couldn't be completed due to a server-side error |

501 | Not implemented | The server doesn't recognize the request (such as an HTTP method that hasn't yet been implemented) | |

502 | Bad gateway | The server is acting as a gateway or proxy and received an error from the downstream server | |

503 | Service unavailable | The server is unable to fulfil the request, perhaps because the server is overloaded or down for maintenance | |

504 | Gateway timeout | The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, did not get a response in time from the upstream server that it needed in order to complete the request |

NOTE

HTTP/1.0 doesn't define any 1xx status codes, but does define the category. Some codes such as (203, 303, 402) are not part of HTTP/1.0

HTTP 2

- Multiplexing

- Stream prioritization

- Binary protocol

- Server push

HTTPS

HTTP is a plain-text protocol. HTTP messages are unencrypted and are readable by any party

Hence, HTTPS a secure version of HTTP was introduced

HTTPS encrypts messages in transit by using the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, though it's often known by its previous incarnation as Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)

HTTPS adds 3 important concepts to HTTP messages:

Encryption: Messages can't be read by third parties while in transit

Integrity: The message hasn't been altered in transit, as the entire encrypted message is digitally signed, and that signature is cryptographically verified before decryption

Authentication: The server is the one you intended to talk to

SSL/TLS

SSL/TLS have 3 goals (CIA):

Confidentiality:

- Provided by Symmetric Encryption

- No man in the middle

Integrity:

- Provided by M.A.C. (Hashing)

- Data should not be tampered and if tampered, the receiver should know about it and discard it

Authentication:

- Provided by Certificates/PKI

CIA of security is used in any of the secure communication protocol such as TLS, IPsec, SSH, etc...

History of HTTP encryption

SSLv1 was never released outside Netscape

SSLv2 and SSLv3 were released in 1995 and 1996 respectively

- SSLv3 was widely used, but in 2014 major vulnerabilities were discovered and support for SSLv3 is not supported by browsers

SSL was standardized as TLS

TLSv1.0 (~SSLv3.1) in 1999, is similar to SSLv3, though not compatible

TLSv1.1 and TLSv1.2 were released in 2006 and 2008 respectively

TLSv1.3 was released in 2018 (current standard)

- TLSv1.0 and TLSv1.1 should not be used (deprecated)

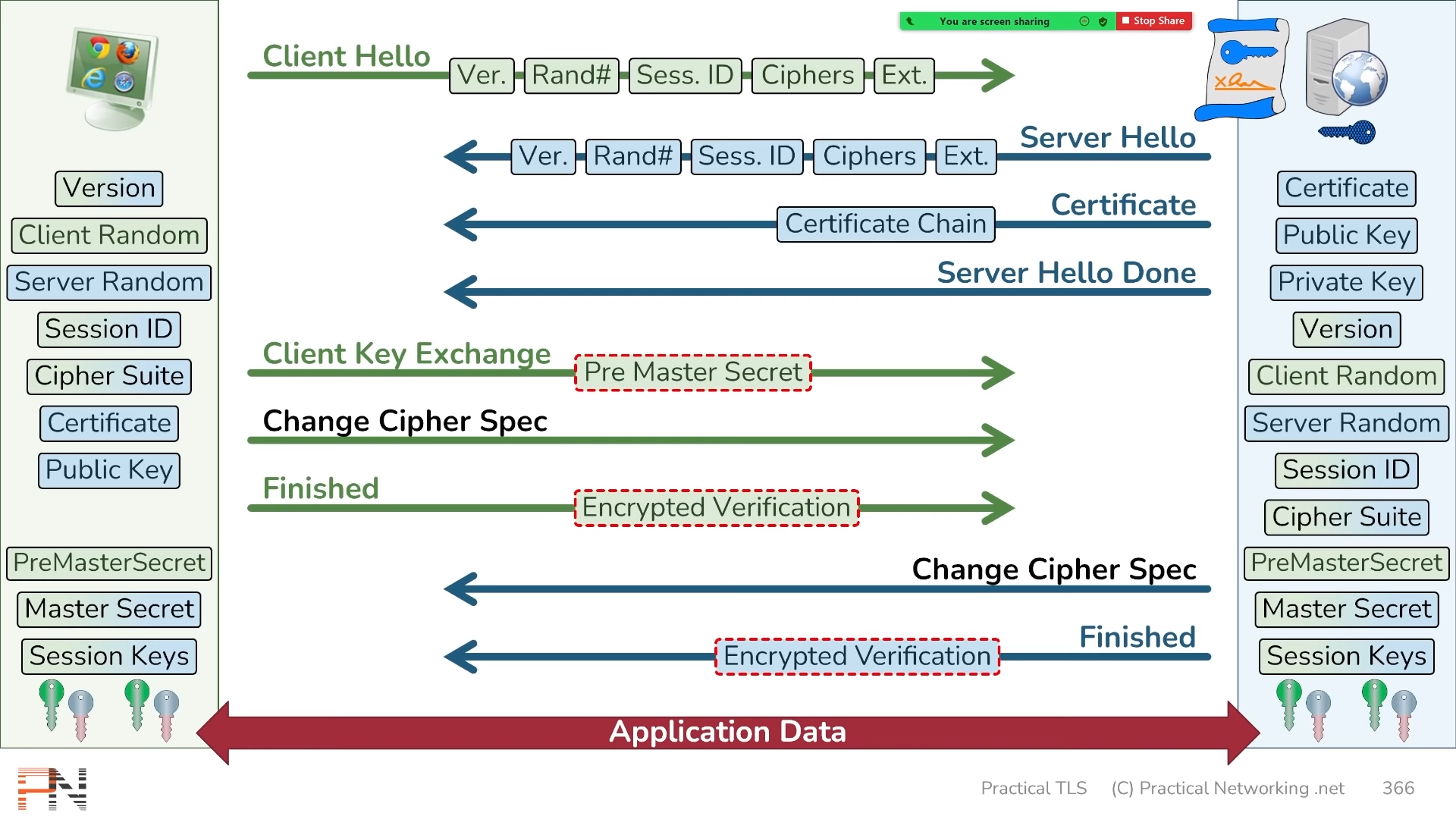

TLS Handshake

- What ciphers will be used?

- Secret Key

- Authentication (Public Key)

- Robust against Man in the middle attacks, Replay attacks, Downgrade attacks, etc...

A TLS handshake is the process that kicks off a communication session that uses TLS. During a TLS handshake, the two communicating sides exchange messages to acknowledge each other, verify each other, establish the cryptographic algorithms they will use, and agree on session keys

Cipher suite picks total four protocols, one for Key-Exchange, Authentication, Encryption, and Hashing:

- Example Cipher Suite string representation

TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256represents:Elliptic-curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDHE): is a key agreement protocol that allows two parties, each having an Elliptic-curve public-private key pair, to establish a shared secret over an secure channel

Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA): is a public-key cryptosystem that is widely used for secure data transmission

AES_128_GCM: Algorithm, Key size, and Operation Mode used for encryption

SHA256: used for hashing

Basic steps of TLSv1.2 Handshake (Total 2 round trips):

TCP Handshake

Client Hello:

- Version: Highest version of TLS/SSL the Client supports

- Random Number (hash) ("client random"): 32 bytes/256 bits

- Timestamp encoded in first four bytes (optional)

- Session ID: 8 bytes/32 bits

0000...all 0's in initial Client Hello

- List of Cipher Suites supported by Client

- Extensions: Optional additional features added to TLS/SSL

Server Hello (server responds with):

- Version: Highest version of TLS/SSL the Server supports

- Random Number (hash) ("server random"): 32 bytes/256 bits

- Timestamp encoded in first four bytes (optional)

- Session ID: 8 bytes/32 bits

- Value generated by Server to identity ensuing Session Keys

- Cipher Suites selected by Server

- If non of TLS version and cipher suite match it sends TLS alert

- Extensions: Optional additional features added to TLS/SSL

Certificate (server sends):

- Server Certificate and Full Certificate Chain

- Includes Server Public Key

Server Hello Done:

- Indicates server has nothing more to send at this time

Client Key Exchange:

Establish Mutual Keying Material (i.e., Seed Value)

Authentication: Client verifies the server's SSL certificate with the certificate authority that issued it. This confirms that the server is who it says it is, and that the client is interacting with the actual owner of the domain

Client generates Pre-Master-Secret (Example using RSA):

- 2 bytes: TLS/SSL Version (optional)

- 46 bytes: Random

Pre-Master-Secret is encrypted using Server's Public Key

- Server can only decrypt if it has Server Private Key

Both parties now have matching Seed Values and hence they both generate all Session Keys:

Seed value used to generate Session Keys (Symmetric Keys)

Pre-Master-Secret used to derive Master Secret

- Master Secret generated using Pre-Master-Secret +

"master secret"+ Client Random + Server Random

- Master Secret generated using Pre-Master-Secret +

Master Secret is used to generate Session Keys, I.V.'s (Client and Server, required by CBC)

- Session Keys generated using Master Secret +

"key expansion"+ Client Random + Server Random

- Session Keys generated using Master Secret +

Generated Session Keys are:

- Client Encryption Key

- Client HMAC Key

- Server Encryption Key

- Server HMAC Key

In the above section calculations involve a PRF (Pseudo Random Function):

- PRF is a Hashing algorithm that generates digests at any desired length

At this point, both parties have identical Session Keys, but they don't know whether the other has the same keys

- Rest of the handshake will prove to both parties that the other party has the correct Session Keys

Change Cipher Spec (client sends): Indicates Client has everything necessary to speak securely

Finished (client sends): Proves to the Serve that Client has correct Session Keys

- Sends an Encrypted Verification

- Client calculates Handshake Hash of all Handshake Records seen so far (Steps 2 to 6) (Prevents downgrade attacks)

- Verification Data (uses PRF)= Master Secret +

"client finished"+ Handshake Hash - Verification Data encrypted with Client Session Keys (Encrypted Verification)

Change Cipher Spec (server sends): Indicates Server has everything necessary to speak securely

Finished (server sends): Proves to the Client that Server has correct Session Keys

- Generates Encrypted Verification using Server Session Keys similar to Step 8, now including Step 8

- Verification Data (uses PRF)= Master Secret +

"server finished"+ Handshake Hash

Start sending application data securely

┌───────────┐ ┌───────────┐

│ Client │ │ Server │

└─────┬─────┘ └─────┬─────┘

│ │

│ │

│ ─────────────────────────► │ ──┐

│ 1. SYN │ │

│ │ │

│ │ │ TCP

│ ◄───────────────────────── │ │

│ 3. ACK 2. SYN ACK │ ──┘

│ │

│ -------------------------- │

│ │

│ ─────────────────────────► │ ──┐

│ 4. ClientHello │ │

│ │ │

│ ◄───────────────────────── │ │

│ 5. ServerHello │ │

│ Certificate │ │

│ ServerHelloDone │ │

│ │ │ TLS

│ ─────────────────────────► │ │

│ 6. ClientKeyExchange │ │

│ ChangeCipherSpec │ │

│ Finished │ │

│ │ │

│ ◄───────────────────────── │ │

│ 7. ChangeCipherSpec │ │

│ Finished │ ──┘TLSv1.3 Handshake:

- Total 1 round trip

- TLS 1.3 does not support RSA, nor other cipher suites and parameters that are vulnerable to attack

- It is faster and more secure

Basic steps:

Client Hello:

- Protocol version

- Client random

- List of cipher suites

- It also includes the parameters that will be used for calculating the premaster secret. Essentially, the client is assuming that it knows the server's preferred key exchange method (which, due to the simplified list of cipher suites, it probably does). This cuts down the overall length of the handshake - one of the important differences between TLS 1.3 handshakes and TLS 1.0, 1.1, and 1.2 handshakes

Server generates master secret:

- At this point, the server has received the client random and the client's parameters and cipher suites

- It already has the server random, since it can generate that on its own. Therefore, the server can create the master secret

Server Hello and "Finished":

- It includes the server's certificate, digital signature, server random, and chosen cipher suite

- Because it already has the master secret, it also sends a "Finished" message

Final steps and client "Finished":

- Client verifies signature and certificate, generates master secret, and sends "Finished" message

Secure symmetric encryption achieved

TLS Handshake Deep Dive and decryption with Wireshark

HTTPS Workings

HTTPS works by using public-key encryption, which allows servers to provide public keys in the form of digital certificates when users first connect. The browser encrypts messages by using this public key, which only the server can decrypt, as only it has the corresponding private key. This system allows us to communicate securely with a website without having to know a shared secret key in advance, which is crucial for a system like the internet, where new websites and users come and go every second of every day

The digital certificates are issued, and digitally signed, by various certificate authorities (CAs) trusted by the browser

- Post

443is used instead of port 80 https://URL scheme is used instead ofhttp://- HTTPS doesn't alter the way HTTP is used in terms of syntax or message format except for the encryption and decryption itself

CERTIFICATES

HTTPS indicates to us that the connection is secure, but does not give any information about the trustworthiness of the server

Benefits of EV or Domain Validated (DV) or Organizational Validated (OV) certificates is highly disputed

- Telnet cannot be used to send HTTPS requests as it dose not handle the encryption and decryption part. So, programs like OpenSSL can be used:

openssl s_client -crlf -connect www.google.com:443 -quiet↵

GET / HTTP/1.1↵

Host: www.google.com↵

↵Drawbacks of HTTP/1.x

- The internet is built upon HTTP/1.x

- Has been functioning reasonably well for a 20-year-old technology

Why websites still take time to load even though the internet speed has increased significantly?

- Broadband speeds have increased, hence decreasing the time taken to download the assets required by the website

- As a result websites should load really fast, but that is not the case. Websites still take time to load

- This is due to the way HTTP/1.x works. HTTP was a request and response based protocol

- Each website makes multiple HTTP requests to get the required assets. These requests are synchronous, i.e. the second request is made only after a response is received for the first request

- Thus website loads slowly if there are many requests being made

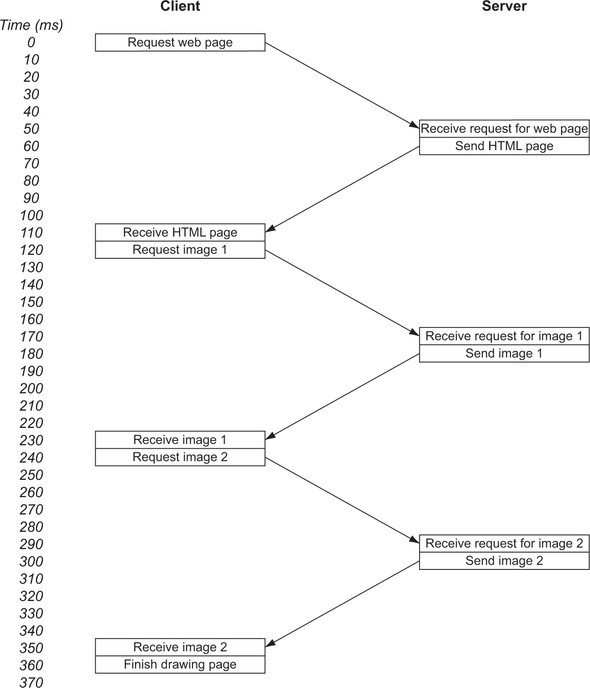

Let us consider a scenario:

Imagine a simple web page with some text and two images

Suppose that a request takes 50ms to reach the web server and the server takes 10ms to respond and the browser takes 10ms to process the response

Now the following steps happen when we request for a web page:

So the total time taken to load the web page was 360ms. Out of which 60ms was spent on processing the requests. And a total of 300ms or 80% of the time, was spent waiting for messages

In this scenario, the browser knows that it requires 2 images. So instead of requesting for both the images, the browser ask for image 1 and waits for the response before asking for image 2

This is an inefficient process. Some browsers open multiple connections to the servers to overcome the waiting process

If the number of assets required by the web page is large then the loading time will increase significantly

- Latency measures how long it takes to send a single message to the server

- Bandwidth measures how much a user can download in those messages

- Latency is the biggest problem of the internet rather than the bandwidth

- Because of increased bandwidths, the size of a typical web page has increased without harming the loading time significantly

- On the other hand, latency has not improved that much. Thus preventing the increase in requests made by the web page without effecting loading time severely

Pipelining for HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 tired to introduce pipelining, which allows concurrent requests to be sent before responses are received so that requests can be sent parallel

The initial HTML still needs to be requested separately, the rest of the requests can be sent concurrently. Thus shaving off 100ms loading time in the previous example

Pipelining should have brought huge improvements to HTTP performance, but for many reasons, it was difficult to implement, easy to break, head-of-line (HOL) blocking, and not well supported by web browsers or web servers

SUPPORT

Pipelining was rarely used

Domain Sharding

Multiple connections are opened to overcome the issues with pipelining. About 6 connections are opened per domain

Websites can serve static contents through sub-domains, thus allowing further 6 more connections per sub-domain. This technique is known as domain sharding

Domain sharding helps to increase performance, reduce HTTP headers such as cookies

Disadvantages:

- Extra memory and processing is required to maintain multiple connections over TCP

- TCP is significantly inefficient

HTTP Compression

The HTTP specification allows the server to compress responses if the client supports compression

It reduces network traffic and increases response speed

If the client supports compression, it will send along the type of compression it can accept:

http<!-- CLIENT --> GET /foo Accept-Encoding: gzip <!-- SERVER --> 200 OK Content-Encoding: gzip <!-- gzipped payload -->

HTTP Caching

Caching involves both the client and the server

Modern default: Don't cache, validate!

Use a CDN to get close to your users

Use

ETagvalidation to save bytes

Opt-in to caching as needed:

- Some assets are immutable (hashes)

Using Service Worker

- Service Workers only run on the 2nd load: and give you a whole extra cache!

- Common pattern: Use Workbox to inject a manifest

- Use a runtime cache for other stuff

- Network or Cache First?

By going Network-First, just fetch new HTML

HTML contains updated hashed asset links: cache misses, but no danger of stale assets

Network-first sites rarely need a reload button

Cache First, you want to load fast at all costs!

But it creates a UX problem, needs reload UX. Obtrusive/confusing (button)

New Web Periodic Background Synchronization API can be used (less support)

If no caching strategy is explicitly specified, browsers will use Heuristic Freshness (the cache can guess a freshness lifetime)

- Without instructions, assets may expire at different times

The server can let the clients know that responses are cacheable in few ways:

- Cache Headers:

The

Cache-Controlheader is the master knob for caching, it holds directives (instructions) - in both requests and responsesmax-age=n: how long asset is valid for, in secondsmust-revalidate: cannot use aftermax-age(optional)public/private: cached by CDNs or just youno-store: don't cache this asset, good for logged in stuffno-cache: cache it, but the response must be validated with the origin server before each reuseimmutable: this file won't change, really- Chrome (after 2017) by default behaves as if

immutableis present - Entry points (such as

index.htmlfiles) shouldn't be marked asimmutable - Cache-busting using version/hashes in URLs of static resources:

- Query strings are marginally safer, as if an old entrypoint refers to

script.js?v=abcdeven if that hash is out of date, they'll still load something

- Query strings are marginally safer, as if an old entrypoint refers to

html<!-- using query string is better --> <script src=https://example.com/react.js?v=18.2></script> <!-- or using hash in the filename --> <script src=https://example.com/react.18.2.js></script>httpCache-Control: public, max-age=604800, immutable- Chrome (after 2017) by default behaves as if

Good defaults:

Cache-Control: max-age=0, must-revalidate, public(always validate)- Great CDNs will invalidate edge caches when you redeploy

- Depending on CDN, you might also have to set

s-maxage(similar tomax-agebut for shared caches, and they will ignoremax-agewhen it is present)

- Depending on CDN, you might also have to set

Example:

Cache-Control: max-age=31536000, immutable(fresh for 1 year = forever as per spec)Cache-Control: max-age=100, must-revalidate(fresh for 100 seconds)Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store(never cache)

Previously the

Expiresheader was also be used to let the client know how long to cache a request:Expires: Mon, 06 Nov 2022 07:42:00 GMT

If a response includes both

Cache-ControlandExpires,Cache-Controltakes priority in determining whether cache data is fresh

How clients determine to serve cached response?

If content is still fresh (based on header value), then return cached content. No call to the server is made

If content is stale (not fresh), then check with the server to see if the cached copy is still valid

Validation headers are included on the outgoing request which lets the server know which version of the resource the client has in the cache

If the server determines that the resource still hasn't changed, it can send back

304 Not Modifiedstatus and updated cache headersCache-Controlwith new freshness info304response dose not include a response body

Validation with

Last-Modifiedheader:- Caching began in 1999

http<!-- INITIAL SERVER RESPONSE --> 200 OK Cache-Control: max-age=100 Last-Modified: Fri, 31 Dec 1999 11:49:59 GMT <!-- CLIENT REQUEST TO CHECK CACHE VALIDITY --> GET /rooms/ref-data If-Modified-Since: Fri, 31 Dec 1999 11:49:59 GMT <!-- SERVER RESPONSE IF CACHE IS VALID --> 304 Not Modified Cache-Control: max-age=100 Last-Modified: Fri, 31 Dec 1999 11:49:59 GMTValidation with

Etagheader (better):ETag: is a fingerprint or hash that uniquely identifies this version of a resourceIf cache is stale, new

ETagvalue is sent to the clientETagvalidation is stronger and more accurate than validation withLast-ModifiedbecauseLast-Modifiedis only accurate down to a second of resolution whereas theETagfingerprint will change anytime a resource is modifiedETagtakes precedence if both are usedIf

ETagmatches, server will respond with304 Not ModifiedstatusSome diminishing returns for small files, as server call needs to happen for validation

http<!-- INITIAL SERVER RESPONSE --> 200 OK Cache-Control: max-age=100 Etag: "88dk35h" <!-- CLIENT REQUEST TO CHECK CACHE VALIDITY --> GET /rooms/ref-data If-None-Match: "88dk35h" <!-- SERVER RESPONSE IF CACHE IS VALID --> 304 Not Modified Cache-Control: max-age=100 Etag: "88dk35h"

Downsides:

One validation might beget another, and so on: Critical Request Chains

- Parallel fetches (e.g., lots of images) aren't an issue: HTTP/2+ solves this

Every small file needs validation

Authentication and Authorization

Send and receive Authentication and Authorization over HTTPS

Authentication: Checking are the users who they say they are?

Authorization: Checking is the user allowed to do this?

Authentication

Authorization Header Format: Used for Authentication (not Authorization)

GET /profile

Authorization: Scheme value...- Servers responds back with status code

401 Unauthorizedif authentication fails

Authentication Schemes:

Basic: username/password (or API key/secret)

- Raw credentials are sent, which can be extremely (always use HTTPS)

Bearer: tokens issued by the server

Digest: (less common) A hash is computed from the client's credentials and some other pieces of the request, like headers, time-stamp, request payload, etc.. Some extra security

What schema to choose depends upon:

- The target audience

- What credentials will they use?

| Developers or Machines | End User Applications |

|---|---|

| Machine to Machine or Service to Service connection | Web sites or Apps where user can enter username and password |

| API keys | - |

| HTTP Basic (if not worried about security) | - |

| OpenID Connect client credentials (better security) | OpenID Connect resource owner password |

| Digest authentication (hard to implement) | Digest authentication (hard to implement) |

OpenID Connect

OpenID Connect resource owner password flow:

Client sends user's credentials (usually username/password) to the server

If credentials are good, the server creates an access token and sends it back to the client

The client can use that access token instead of the raw credentials to make authenticated requests to the API

The token is placed in the Authorization header with a Bearer scheme

The OpenID Connect client credentials flow is very similar except a client would exchange an API key in secret instead of a username and password for a token

HTTP Security

DNS Hijacking

- Attacker changes DNS records of target to point to own IP address

- All site visitors are directed to attacker's web server

- Motivation

- Phishing

- Revenue through ads, cryptocurrency mining, etc...

How do they do it?

- Malware changes user's local DNS settings: like the

hostsfile - Hacked recursive DNS resolver

- Hacked router

- Hacked DNS Nameserver

- Compromised user at DNS provider

- TLS verification can be completed using Let's Encrypt that says this server is legit

DNS Privacy

Queries are in plaintext

ISPs have been known to sell this data

DNS-over-HTTPS

DNS SETTING

Consider switching your DNS settings to Cloudflare (1.1.1.1) or another provider with a good privacy policy

Tools

There are many tools that can be used to create a TCP/IP connection, hence the same tools can be used to send a HTTP request

Some of the tools are:

Telnet: It opens a TCP/IP connection to a server

bashprintf 'HEAD / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: en.wikipedia.org\r\n\r\n' | nc en.wikipedia.org 80printf- Similar tocatbut smarternc- netCat is used to talk to internet

Openssl: Can be used to for HTTPS connection

WARNING

HTTP is not based on Ping. Ping is much simpler than HTTP

HTTP Proxy Servers

- Can cache content

- Can block content (e.g. malware, adult content)

- Can modify content

- Can sit in front of many servers ("reverse proxy")