Git

It is a distributed Version Control System (VCS). Version control is a way to save changes over time without overwriting previous versions (Version Control is a system which records the changes made to a file so that you can recall a specific version later)

It helps in tracking changes in the project and coordinating work on those files among multiple people

- VCS also know as Source Code Management (SCM)

Types of Version Control Systems:

Local: It allows you to copy files into another directory and rename it (For example, project.1.1). This method is error-prone and introduces redundancy

Centralised: All version files are present in a single central server. For example, CVS, SVN, and Perforce

Distributed: All changes are available in the server as well as in local machines. Being distributed means that every developer working with a Git repository has a copy of that entire repository. For example, Git and Mercurial

History

Old VCS that predate Git:

Source Code Control System (SCCS):

- 1972: closed source, free with Unix

- Stored original version and sets of changes

Revision Control System (RCS):

- 1982: open source

- Stored latest version and sets of changes

Concurrent Version System (CVS):

- 1986-1990: open source

- Multiple files, entire project

- Multi-user repositories

Apache Subversion (SVN):

- 2000: open source

- Track text and images

- Track file changes collectively (track directory)

BitKeeper SCM:

- 2000: closed source, proprietary

- Distributed version control

Git:

- April 2005

- Linus Tovalds

- Distributed version control

- Open source and free software

- Faster than other SCMs (100 times in some cases)

- Better safeguards against data corruption

Distributed Version Control

- Different users maintain their own repositories

- No central repository

- Changes are stored as change sets:

- Track changes, not versions

- Different from CVS and SVN, which tracked versions

- Change sets can be exchanged between repositories

- "Merge in change sets" or "apply patches"

- No single master repository

- Many working copies

- No need to communicate with a central server

- No network access required

- No single failure point

Git Internals

Git uses 3 Tree architecture:

- Repository

- Staging Index

- Working

These 3 stages are:

| # | Stages | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Working Directory | Un-tracked new files and modified directories are found here. |

| 2 | Staging Area | Things we want to commit and ignore which we don't want. |

| 3 | Remote Repository | .git directory(Repository) |

The .git folder contains different files and folders:

hooks/:info/:objects/:ref/:config: file contains configurations specific to that repositorydescription:HEAD: A link to a point inlogs/: Created after first commit,index: Created after first commit,COMMIT_EDITMSG: Created after first commit,

The objects folder consists of 4 types of objects:

- Blob (Binary large object): Copy of contents of the file

- Tree

- Commit: Creates a snapshot of the project at a given point

- Annotated tag

git cat-file: Provide content or type and size information for repository objects:bash# find the type of object git cat-file -t [commitSHA] # see file content git cat-file -p HEAD:"[filename]"

Repositories

When working on a Git project most of the time the user will have to deal with two repositories:

Remote Repository: They are versions of your project that are hosted on the Internet or network somewhere

Local Repository: It is a copy of the remote repository that exists on the user's workstation. This is the repository where the user works on the project

Head

HEAD is a reference variable that always points to the tip of your current (working) branch, that is, recent commit of your current branch

The

HEADfile inside the.git/directory holds the reference valuebashcat .git/HEAD # output # ref: refs/heads/master cat refs/heads/master # returns a SHA value which is the # SHA of a commit to which HEAD currently points to

HEAD can be used with the following symbols to refer to other commits:

- Tilde symbol (

~): Used to point to the previous commits from base HEAD - Caret symbol (

^): Used to point to the immediate parent commit from the current referenced commit

Usage:

- HEAD: current branch

- HEAD^: parent of HEAD

- HEAD~4: the great-great grandparent of HEAD

The git commands that require commit-hash will default to HEAD if no commit-hash is provided

Dot Operators

Installation

Git can be installed on the most common operating systems like Windows, Mac, and Linux

Download Git from this link and install it

Configuration

All the Git configurations are stored in a file:

The configurations specific to the users resides in home directory as

~/.gitconfigor~/.config/git/configfile- To add configurations to this file we pass

--globaloption in the CLI

- To add configurations to this file we pass

The configurations specific to a repository resides as

.git/configfile- To add configurations to this file we pass

--localoption or justgit configin the CLI

- To add configurations to this file we pass

The configurations specific to that machine resides as

/etc/gitconfigfile- To add configurations to this file we pass

--systemoption in the CLI

- To add configurations to this file we pass

The priority in which these configuration files are used is: local > global > system

Git configuration commands:

# list all configurations

git config --list

# check specific configuration

git config [config name]

git config user.name

# check in which file a specific configuration resides

git config --show-origin [config name]

git config --show-origin user.nameFor the initial setup the user must provide their identity such as full name and email address, this is required as it helps in identifying the person making the commits (saving changes)

bash# add username and email git config --global user.name "First Last" git config --global user.email "myemail@domain.com" # change the core editor git config --global core.editor [editor name] git config --global core.editor vim # colourize user interface (might be on by default) [true, auto] git config --global color.ui true

We can modify configurations from the CLI or by directly modifying the configuration file

Add this to automatically create a new upstream branch for your local branch

bashgit config --global push.autoSetupRemote true

WINDOWS

In windows Git looks for .gitconfig file in $HOME directory (C:\Users\$USER)

Attributes

A .gitattributes file is a simple text file that gives attributes to pathnames

- The

.gitattributesfile allows you to specify the files and paths attributes that should be used by git when performing git actions

Example:

- Use

exiftoolto diff metadata ofpngfiles:

# take every file that ends in png

# and pre-process them with a strategy called `exif`

echo '*.png diff=exif' >> .gitattributes

# the `exif` strategy is to run exiftool on the file

git config diff.exif.textconv exiftoolSSH

Set-up SSH keys for authenticating to a remote repository hosting service:

ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "string"Git Commands

Git was initially a toolkit for a VCS and hence consists of a number of subcommands divided into:

Plumbing: Subcommands that do low-level work and were designed to be chained together UNIX-style or called from scripts

- Around 63 commands

- 19 manipulators (

apply,commit-tree,update-ref, ...) - 21 interrogators (

cat-file,for-each-ref, ...) - 5 syncing (

fetch-pack,send-pack, ...) - 18 internal (

check-attr,sh-i18n, ...)

Porcelain: More user-friendly commands

- Around 82 commands

- 42 main commands (

add,commit,push,push, ...) - 11 manipulators (

config,reflog,replace, ...) - 17 interrogators (

blame,fsck,rerere, ...) - 10 inter-actors (

send-email,p4,svn, ...)

- There are around 145 commands

Help

You can get information about any of the Git commands by:

git help [git command name]

git help config

# or

git [git command name] --help

git config --help

# or

man git-[command name]

man git-configInitialize Git

This command can be used:

- To create a new project with Git

- Or initializes the current folder to track its changes by Git:

# transform the current directory into a git repository

git init

# transform a directory in the current path into a git repository

git init [directory name]

# create a new bare repository

git init --bare

# create shared repository

git init --bare --shared=allThe above command creates a hidden .git folder. That directory stores all of the objects and refs that Git uses and creates as a part of your project's history

This hidden .git directory is what separates a regular directory from a Git repository

Clone Repository

Git clone gets the complete project from remote to your local machine (used to create a copy of a specific repository or branch within a repository)

git clone [repo https url/ssh link]

# you can also provide your own repo name

git clone [repo https url/ssh link] [repo name]

# clone a repository but without the ability to edit any of the files

git clone --mirror

# clone only a single branch

git clone --single-branch

# partial cloning

# get only the last commit and the objects it needs

git clone --depth=1

# to get rest of the history later run

git fetch --unshallow

# if you want to do a blobless or treeless clone

# it will bring data as needed (`git blame`, etc. will fetch data)

git clone --filter=blob:none

git clone --filter=tree:0git init vs git clone:

git init: One Person Starting a New Repository Locally or Initializing Existing Foldergit clone: The Remote Already Exists

Remote Repository

When we clone a remote repository, a reference of that remote repository will be added to your local repository configuration. This reference is used to communicate changes between the local repository and the remote repository

- URL can be HTTPS or SSH

# list all remote connections

git remote

# list all remote connections with URL

git remote -v

# add new remote connection

git remote add [name] [URL]

# remove a remote connection

git remote remove [name]

# change remote connection URL

git remote set-url [URL]

# rename a remote connection

git remote rename [old-name] [new-name]When a repo is clone a default remote URL is added with the name origin. And if the repository has multiple remotes then typically the new URL is added with the name upstream

Remove Git Tracking

To remove Git tracking from the project, just delete the hidden .git folder

rm -rf .gitNOTE

If you remove this folder you will permanently loose the project history, unless you have a remote copy

Status

Displays the current state of the staging area and the working directory, that is, which files are added/removed/modified in the working directory and which files are staged

git status

# give output in short format

git status -s

# "verbose" output

git status -v

# get short status with branch name

git status -sbAdd File

Adds new or changed files in your working directory to the Git staging area. If you have added a new file, Git starts tracking that file

Staging area is like a rough draft space, where files are placed for the next commit

You can select all files, a directory, specific files, or even specific parts of a file for staging and committing

git add [filename]

# add the entire directory recursively,

# including files whose names begin with a dot

git add

git add -A

# stage modified and deleted files only, not new files

git add -u

# interactively stage hunks of changes (patch)

git add -pAdd empty directory, as Git ignores empty directories:

- Add a dot file inside the directory:

.gitkeep

Interactive Staging

- Stage changes interactively

- Allows staging portions of changed files

- Helps to make smaller, focused commits

git add --interactive

git add -iPatch Mode:

- Allows staging portions of a changed file

- "Hunks": an area where two files differ

- Hunks can be staged, skipped, or split into smaller hunks

Split a Hunk (automatically):

- Hunks can contain multiple changes

- Tell Git to try to split a hunk further

- Requires one or more unchanged lines between changes

Edit a Hunk (split manually):

- Hunk can be edited manually

- Most useful when a hunk cannot be split automatically

- Diff-style line prefixes:

+,-,#,space

Commit

Create a commit, which is like a snapshot of your repository. These commits are snapshots of your entire repository at specific times

Make new commits often, based around logical units of change

Over time, commits should tell a story of the history of your repository and how it came to be the way that it currently is

Commits include lots of metadata in addition to the contents and message, like the author, timestamp, and more

Each commit contains an unique hash number

To view the details of a commit including the metadata and the changes made in the commit use the git show command

# start commit process

git commit

# include commit message and body at the same time

git commit -m [commit message]

git commit -m [commit message] -m [commit body]

# interactively commit hunks of changes (patch)

git commit -p

# replace the most recent commit with a new commit

git commit --amend

# amend commit with new message

# if no file changes are there this will just update the commit message

git commit --amend -m "NEW MESSAGE"Git commit amend should be used only if:

- That commit hasn't been pushed to the remote yet

- There is a spelling error in the commit message

- It doesn't contain the changes that you'd like to contain

NOTE

Amending commits is not advisable. It changes the commit-hash and hence changing the history

Fix-up commits:

- You have 3 commits and you raised a pull request from that branch

- There was a comment to make some changes in a file, suppose this file changes were part of first commit, you can either make the changes and create a new commit or modify the first commit

commit --fixupcan help you with fix a particular commit

git commit --fixup=[commitSHA]

git rebase --autosquash [branch]Make Atomic commits:

- Small commits

- Only affect a single aspect

- Easier to understand, to work with, and to find bugs

- Improves collaboration

Commit best practice:

- Add the right changes

- Compose a good commit message:

- Subject (50 chars): concise summary of what happened

- Body (150 chars): mode detailed explanation:

- What is now different than before?

- What's the reason for the change?

- Is there anything to watch out for/anything particularly remarkable?

Example: Angular commit convention

<type>(<scope>): <short summary>

│ │ │

│ │ └─⫸ Summary in present tense. Not capitalized. No period at the end

│ │

│ └─⫸ Commit Scope: animations|bazel|benchpress|common|compiler|compiler-cli|core|

│ elements|forms|http|language-service|localize|platform-browser|

│ platform-browser-dynamic|platform-server|router|service-worker|

│ upgrade|zone.js|packaging|changelog|docs-infra|migrations|ngcc|ve|

│ devtools

│

└─⫸ Commit Type: build|ci|docs|feat|fix|perf|refactor|testTypes:

build: Changes that affect the build system or external dependencies (example scopes:gulp,broccoli,npm)ci: Changes to our CI configuration files and scripts (examples:CircleCi,SauceLabs)docs: Documentation only changesfeat: A new featurefix: A bug fixperf: A code change that improves performancerefactor: A code change that neither fixes a bug nor adds a featuretest: Adding missing tests or correcting existing tests

Pull

It updates your current local working branch and all of the remote tracking branches

git pullis a combination ofgit fetch+git merge, updates some parts of your local repository with the changes from the remote repository

# update local with commits from remote

# (merge is used)

git pull

# update from a specific remote branch

git pull --force

# fetch all remotes

git pull --all- Run

git pullregularly

Pull Rebase:

- Fetch from remote, then rebase instead of merging

- Keeps history cleaner by reducing merge commits

- Only use on local commits not shared to a remote

# update but rewrite history so any local commits occur after all new commits

git pull --rebase

git pull --rebase=preserve

git pull --rebase=interactivePull Requests: Not core Git feature, but provided by Git hosting platforms

- communicating about and reviewing code

- appeal request invites reviewers to provide feedback before merging

- contributing code to other repositories, to which you don't have write access. Contributing to an open source repository

- Fork is your personal copy of a GIT repository

Checking out pull requests locally:

# Provide pull request ID

git fetch origin pull/ID/head:NewLocalBranchName

# Switch to the newly created branch

git checkout [branch]Issues:

error: some local refs could not be updated, to resolve this first prune remote branches, then pull

git -c fetch.parallel=0 -c submodule.fetchJobs=0 pull --progress "origin" +ref/heads/masterMerge

Git Merge dose not provide a dry run option, so we can do this:

# pass --no-commit to stop auto commit

# and also stopping fast-forward with --no-ff

git merge --no-commit --no-ff $BRANCH

# to examine the staged changes

git diff --cached

# and you can undo the merge, even if it is a fast-forward merge

git merge --abortMerge Conflicts occur when contradictory changes happen:

git mergegit rebasegit pullgit stash applygit cherry-pick

Git can remember the resolution for a given merge conflict if it was previously resolved

# git REuse REcorded REsolution

git config --global rerere.enable true

# you can further ask it to automatically stage it for you with

git config --global rerere.autoUpdate truePush

It uploads all local branch commits to the corresponding remote branch

git push

# pushing new branch, this creates an upstream tracking branch

git push -u origin [branch]

# push all branches

git push --all

# safe force pushing

git push --force-with-lease

# alias it with

git config --global alias.fpush push --force-with-lease

# force push (only if you want to override)

git push -fGenerally most of us don't love doing forced pushes, because there is always a chance that you're overwriting someone else's commits. Let's take a scenario:

You commit and push something to GitHub

Someone else pulls it down, commits something and pushes it back up

You amend a commit, rewriting the history, and force push it, not knowing that anyone had based something off your work

This effectively removes what the other person had done

What you really want to do is check to see if anyone else had pushed and only force push if the answer is no. However, there is always a bit of a race condition here because even if you check first, in the second it takes you to then push, something else could have landed from elsewhere in the meantime

So, Git has created a new force pushing option called --force-with-lease that will essentially check that what you last pushed is still what's on the server before it will force the new branch update

Reasons to force push:

- Local version is better than the remote version

- Remote version went wrong and needs repair

- Versions have diverged and merging is undesirable

NOTE

Use force push with extreme caution. Disruptive for others using the remote branch. Commits disappear. Subsequent local commits are orphaned for others

Rename File

Change file name or file path and prepare it for commit

git mv [original filename] [new filename]Delete Files

Delete the file from the working area or staging area and add the deletion to the staging area

git rm [filename]Remove (untrack) a file from version control but preserve the file locally:

git rm --cached [filename]Patch

Create Diff Patches:

- Share changes via files

- Useful when changes are not ready for a public branch

- Useful when collaborators do not share a remote

- Discussion, review, approval process

# direct output to a file

git diff [from-commit] [to-commit] > [output-name].diffApply Diff Patches:

- Apply changes in a diff patch file to the working directory

- Makes changes, but not commits

- No commit history transferred

git apply [filename].diffCreate Formatted Patches:

- Export each commit in Unix mailbox format

- Useful for email distribution of changes

- Includes commit messages

- One commit per file by default

# export all commits in the range

git format-patch [start-commitSHA]..[end-commitSHA]

# export all commits on current branch

# which are not in master branch

git format-patch master

# export a single commit

git format-patch -1 [commitSHA]

# put patch files into a directory

git format-patch master -o [directory-name]

# output patches as a single file

git format-patch master --stdout > [filename].patchApply Formatted Patches:

- Extract author, commit message, and changes from a mailbox message and apply them to the current branch

- Similar to cherry-picking: same changes, different SHAs

- Commit history is transferred

# apply single patch

git am [directory-name]/[patch-filename].patch

# apply all patches in a directory

git am [directory-name]/*.patchGit Clean

Git clean undoes files from the repository. It primarily focuses on untracked files

- Remove untracked files

# do a dry run

git clean -n

# remove untracked files

git clean -f

# remove untracked directories

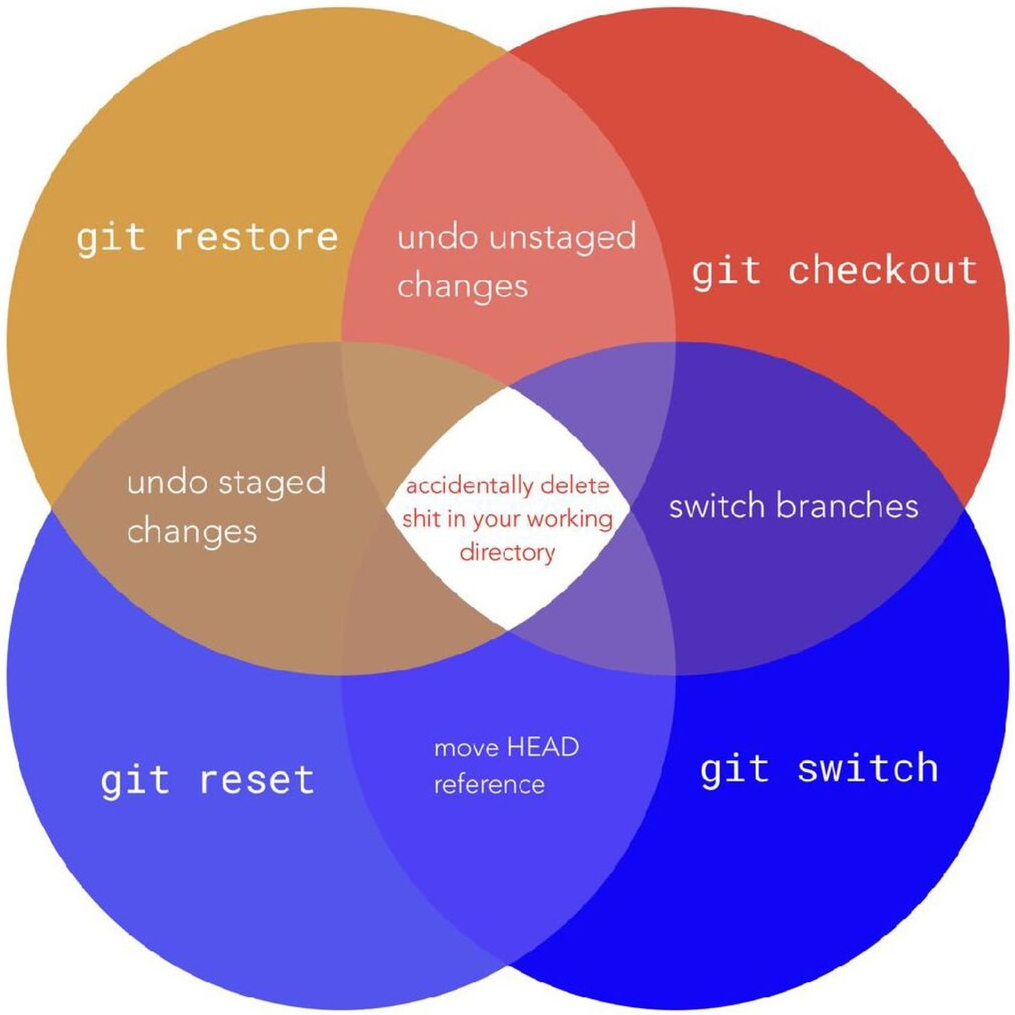

git clean -fdRestore

Restore specified paths in the working tree with some contents from a restore source. If a path is tracked but does not exist in the restore source, it will be removed to match the source

git restore [filename]

# same as

git checkout [filename]

git restore --source HEAD@{10.minutes.ago} [filename]

git restore -p [filename]Restore a deleted file which was tracked by git

Find the commit where the file was deleted:

bashgit rev-list -n 1 HEAD -- [filename]Checkout to that commit to get the file back:

bashgit checkout [commitSHA]^ -- [filename]

Ignoring File

Untracked files or folders can be ignored so that Git dose not track them. For that create a file named .gitignore and add all the file or folder listing patterns

We can use:

Pattern matching (basic regular expressions):

*?[aeiou][0-9]logs/*.txt

Negative expressions:

*.php!index.php

Add comments using

#Blank lines are skipped

Example:

# ignore all .a files

*.a

# but do track lib.a, even though you're ignoring .a files above

!lib.a

# only ignore the TODO file in the current directory, not sub-dir/TODO

/TODO

# ignore all files in a directory named build

# add a trailing slash

build/

# ignore doc/notes.txt, but not doc/server/arch.txt

doc/*.txt

# ignore all .pdf files in the doc/ directory and any of its subdirectories

doc/**/*.pdfLists all ignored files in this project

bashgit ls-files --other --ignored --exclude-standard

Ideas on what to ignore:

- Compiled source code

- Packages and compressed files

- Logs and databases

- OS generated files

- Useful .gitignore templates

Globally ignore files:

- Ignore files in all repositories

- Settings are not tracked in repo

- User specific instead of repository specific

git config --global core.excludesfile ~/.gitignore_globalLog

- Log is the primary interface to Git

- Log has many options

- Sorting, filtering, output formatting

List version history for the current branch:

git log

# useful for visualizing branches

git log --graph --all --decorate --oneline

# list commits as patches (diffs)

git log --patch

# list edits to lines 100-150 in filename.txt

git log -L 100,150:filename.txt

# Use heuristics to get log of a certain function, class, etc..

git log -L :funcName:filename.ts

# get logs contains an expression

git log -S some_word -pList version history for a file, including renames:

git log --follow [filename]- Speed up the process of log by:

git commit-graph write

# run it as part of maintenance

git config --global fetch.writeCommitGraph trueBranch

# create new branch

git branch [branch]

# list all branches

git branch -a

# rename branch

git branch -m [name]

# delete a branch

git branch -d [branch]

git branch -D [branch]

# delete branch from remote repo

git push origin -d [remote] [branch] # git v2.8.0+

git push origin --delete [remote] [branch] # git v1.7.0+

git push origin :[remote_branch] # old way

# see all the merged branches

git branch --merged

# merge branch (from the branch to merge into)

git merge [other branch]

# split into columns to make better use of the screen real estate

git branch --column

# sort by objectsize, authordate, committerdate, creatordate, or taggerdate

git branch --sort committerdateGit branch configurations:

# set column mode by default

git config --global column.ui auto

# sort branches by

git config --global branch.sort -committerdate- To delete a branch, current must be on a different branch

- To delete a branch hows commits are not merged use

-Dflag

Identify merge branches:

- List branches that have been merged into a branch

- Useful for knowing what features have been incorporated

- Useful for clean-up after merging many features

# list branches merged into the current branch

git branch --merged

# list branches not merged into the current branch

# branches that have commits that are not merged

# into current branch

git branch --no-merged

# list remote branches merged into the current branch

git branch -r --mergedCheckout Branching Strategies

Prune Stale Branches

- Delete all stale remote-tracking branches

- Remote-tracking branches, not remote branches

- Stale branch: a remote-tracking branch that no longer tracks anything because the actual branch in the remote repository has been deleted

Remote branches:

- Branch on the remote repository (bugfix)

- Local snapshot of the remote branch (origin/bugfix)

- Local branch, tracking the remote branch (bugfix)

# delete stale remote-tracking branches

git remote prune origin

git remote prune origin --dry-run

# prune while fetching

# prune, then fetch

git fetch --prune

# always prune before fetch

# destructive

git config --global fetch.prune trueReset

Git reset as the name suggests resets things. Reset the working area to a specific commit

It can undo the changes that are already committed

# reset local working directory to

# remote branch head

git reset --hard origin/master

# un-stages the file, but preserve its contents

# move file from staging area back to working directory

git reset [filename]

# or

git reset HEAD [filename]

# discard changes

git reset --hard

# reset everything to the latest snapshot

git reset --hard HEAD

# undoes all commits after [commit], preserving changes locally

git reset [commit]

# discards all history and changes back to the specified commit

git reset --hard [commit]

# interactively reset hunks of changes (patch)

git reset -pReset commit with the following options:

--soft: Moves the commit changes into staging area and does not affect the current working area--hard: Deletes all the commit changes. Be cautious with this flag. Might lose all changes from both staging and working area to match the commit--mixed: Default operation. Moves commit changes to the working area

Apply reset command on:

- Staged files

- Commits

Reset last Rebase or Merge

# undo, unless ORIG_HEAD has changed again

# (rebase, reset, merge change ORIG_HEAD)

git reset --hard ORIG_HEADNOTE

Use revert whenever possible

Revert

Undo changes made in a commit (revert a commit)

Git revert is similar to reset however, git revert inverses the changes from that old commit and creates a new revert commit

- A new commit is made which contains the changes needed to revert a commit

git revert [commitSHA]Diff

Compares contents of the working directory with the staging area

git diff

# show words that changed

git diff --color-words

# get word diffs

git diff --word-diffCompare staging to the HEAD of the branch of the repository:

git diff --cached

# or use its alias

git diff --stagedCompare changes of a file between current state and last commit:

git diff [filename]

# using tags

git diff [tag-name-1]...[tag-name-2]Compare two branches:

git diff [first branch]...[second branch]TOOL

We can use a GUI tool or an external diff viewing program

git difftoolTo get help and add your preferred tool:

git difftool --tool-help

# ADD A TOOL

git difftool --tool=[tool]Checkout

Git checkout is used to switch. Switch between branches, commits, and files (it dose a lot, if you need is to switch branch use switch)

# checkout branch

git checkout branchGo to a specific snapshot (commit)

- This command creates a detached head, meaning, this will give a temporary branch to work and debug. Line being on an unnamed branch

- Do not commit in this temporary branch. As new commits will not belong to any branch

- Detached commits will be garbage collected (~2 weeks)

git checkout [commitSHA]- To preserve commits made in detached head state:

# tag the commit (HEAD detached)

git tag [tag name]

# create a branch (HEAD detached)

# but the detached HEAD needs to be reattached

# to this new branch

git branch [new_branch]

# better option is to create a branch and reattach HEAD

git checkout -b [new_branch]Undo or revise old changes: You can pull a snapshot of a file from old commit and work on it with the intent to commit the new changes:

- Go back to the head:

git checkout master

# discard changes of a file in working area

git checkout [filename]

# checkout older version of the file

git checkout HEAD@{10.minutes.ago} -- [filename]

# interactive patch restore

git checkout -p [filename]- The file will be put into staging area

git checkout [commitSHA] -- [filename]You can apply checkout command on:

- Working file

- Commit

Git command commonalities:

Switch

Switch to a specified branch. The working tree and the index are updated to match the branch. All new commits will be added to the tip of this branch

- Alternate commands to checkout

git switch branch

# same as

git checkout branchgit switch -c [new_branch]

# same as

git checkout -b [new_branch]Fetch File

Fetch all:

# fetch commits and tags

git fetch

# fetch only tags (with necessary commits)

git fetch --tags

# fetch all

git fetch --progress --all

# prune, then fetch

git fetch --pruneRebase Commits

- Take commits from a branch and replay them at the end of another branch

- Useful to integrate recent commits without merging

- Maintains a cleaner, more linear project history

- Ensures topic branch commits apply cleanly

# rebase current branch to tip of master

git rebase master

# rebase new_feature to tip of master

git rebase master new_feature

# return commit where topic branch diverges

git merge-base master new_feature

# interactive rebase

git rebase -i

# rebasing stacks

git rebase --update-refs

# make this option set globally

git config rebase.updateRefs trueThe Golden Rule of Rebasing:

- Thou shalt not rebase a public branch

- Rebase abandons existing, shared commits and creates new, similar commits instead

- Collaborators would see the project history vanish

- Getting all collaborators back in sync can be a nightmare

Merging vs. Rebasing

- 2 ways to incorporate changes from one branch into another branch

- Similar ends, but the means are different

| Merging | Rebasing |

|---|---|

| Adds a merge commit | No additional merge commit |

| Non-destructive | Destructive: SHA changes, commits are rewritten |

| Complete record of what happened and when | No longer a complete record of what happened and when |

| Easy to undo | Tricky to undo |

| Logs can become cluttered, non-linear | Logs are cleaner, more linear |

How to choose?

- Merge to allow commits to stand out or to be clearly grouped

- Merge to bring large topic branches back into master

- Merge anytime the topic branch is already public and being used by others (The Golden Rule of Rebasing)

- Rebase to add minor commits in master to a topic branch

- Rebase to move commits from one branch to another

Handle Rebase Conflicts

- Rebasing creates new commits on existing code

- May conflict with existing code

- Git pauses rebase before each conflicting commit

- Similar to resolving merge conflicts

# after resolving the conflict use

# --continue to commit and proceed to next commit

git rebase --continue

# skipping a commit

git rebase --skip

# abort rebase

git rebase --abortRebase onto other branches

git rebase --onto [new-base] [upstream-branch] [branch]Undo Rebase

- Can undo simple rebases

- Rebase is destructive

- Undoing complex rebases may lose data

- Use git reset

Or rebase back to former merge-base SHA:

# undo by rebasing to former merge-base SHA

git rebase --onto [merge-base-SHA] [merge-base] [branch]Interactive Rebasing

- Chance to modify commit as they are being replayed

- Opens the

git-rebase-todofile for editing - Can reorder or skip commits

- Can edit commit contents

Options:

pick,dropreword,editsquash,fixupexec

# interactive rebase

git rebase -i master new_feature

# rebase last 3 commits onto the same branch

# but with the opportunity to modify them

git rebase -i HEAD~3Squash Commits:

- Fold two or more commits into one

squash: combine change sets, concatenate messagesfixup: combine change sets, discard this message- Uses first author in the commit series

Cherry-Pick

The cherry-pick command takes changes from a specified commit and places them on the HEAD of the currently checked-out branch

- Apply the changes from one or more existing commits

- Can be used to apply commit from one branch to another

- Each existing commit is recorded as a new commit on the current branch

- Conceptually similar to copy-paste

- New commits have different SHAs

git cherry-pick [commitSHA]

# cherry-pick multiple commits

git cherry-pick [commitSHA1] [commitSHA2]

# cherry-pick range of commits

git cherry-pick [commitSHA-of-3]..[commitSHA-of-5]

# edit the commit message

git cherry-pick [commitSHA] --edit

# cherry-pick without committing

git cherry-pick [commitSHA] --no-commit

# add the changes to the staging area and continue with the cherry-pick

git cherry-pick --continue

# abort the cherry-pick

git cherry-pick --abortCannot cherry pick a merge commit as merge commits have two parents

Use

-mflag to specify the parent if cherry-picking merge commitbashgit cherry-pick [commitSHA] -m [parent-number]Can result in conflicts which must be resolved (same as merge conflicts)

Stash

Git stash temporarily saves the changes made in working directory and work on some other changes

# save current changes

git stash

# save with a message

git stash save [message]

# retrieve the saved changes (it will not remove the stash from the list)

git stash apply [stash@{id}]

# get the list of all stashes

git stash list

# get the latest stash and apply it in the working area

git stash pop [stash@{id}]

# delete a stash

git stash drop [stash@{id}]

# interactively stash hunks of changes (patch)

git stash -pNOTE

Git stash is branch agnostic. All branches use the same stash list. This is helpful when moving the changes from one branch to another branch

UNTRACKED FILES

By default, Git will not stash changes made to untracked or ignored files

# TO STASH UNTRACKED FILES

git stash -u or --include-untracked [filename]Show

Outputs metadata and content changes of the specified commit

git show [commitSHA]

# using tags

git show [tag-name]Allows us to see git objects details:

git show [object-sha]

git show --pretty=raw [object-sha]ls-tree

Show the object details:

git ls-tree [object-tree-sha]Output:

FILE PERMISSIONS / TYPE OF FILE / objectSHA / FILE NAME

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 README.mdReflog

Git reflog has the superpower to track the head

The difference between log and reflog is that:

git logwill track every commit that you make and record it as a snapshot at a particular time, whereasgit reflogwill keep track of commits that are made as well as the commits that are discarded

This is provided in a rolling buffer for 30 days

The

git reflogcommand will list down the logs whenever the HEAD changes like the branch was created, cloned, checked-out, renamed, or any commits made on the branch

git reflog

git for-each-ref --sort=-committerdate --format="%(color:blue)%(authordate:relative) %(color:red)%(authorname) %(color:white)%(color:bold)%(refname:short)" refs/remotesBlame

Shows what revision and author last modified each line of a file

- Browse annotated file

- Determine who changed which lines in a file and why

- Useful for probing the history behind a file's contents

- Useful for identifying which commits introduced a bug

# annotate file with commit details

git blame [filename]

# ignore white space

git blame -w [filename]

# annotate lines 100-105

git blame -L 100,105 [filename]

git blame -L 100,+5 [filename]

# detect lines moved or copied in the same commit

git blame -C [filename]

# or the commit that created the file

git blame -C -C [filename]

# or any commit at all

git blame -C -C -C [filename]

# annotate file at revision commitSHA

git blame [commitSHA] [filename]

git blame [commitSHA] -- [filename]

# similar to blame, different output format

git annotate [filename]Options:

-s: to suppress the author's name and time stamp from the output-e: to show the author's email instead of the author's name-f: to show the filename in the original commit-n: to show the line number in the original commit

Bisect

Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

- Find the commit that introduced a bug or regression

- Mark last good revision and first bad revision

- Resets code to mid-point

- Mark as good or bad revision

- Repeat

Git bisect will:

- Perform a binary search in the commits

- Allow us to check it manually

- Allow us to declare its status as good or bad

Steps: start, bad, good

Start bisecting:

bash# start bisect session git bisect startMark the current commit as bad:

bashgit bisect badProvide a commit/branch/tag to start from:

bashgit bisect good [treeish]Now add the current commit as bad, Git will go through all the commits between the start commit and the current bad commit

bashgit bisect bad or git bisect bad [treeish]

From now check the application and verify if the application has the bug or not, if the commit dose not have bug then mark it as good and if you find the commit that has the bug then mark it as bad. Repeat this process till the tool narrows down to the commit that introduced the bug

git bisect log: To find the flow of Git Bisect, that is, to see what has been done so fargit bisect reset: To reset if something went wrong

Prune

Prune all unreachable objects

# do not need to use!

git prune

# part of garbage collection

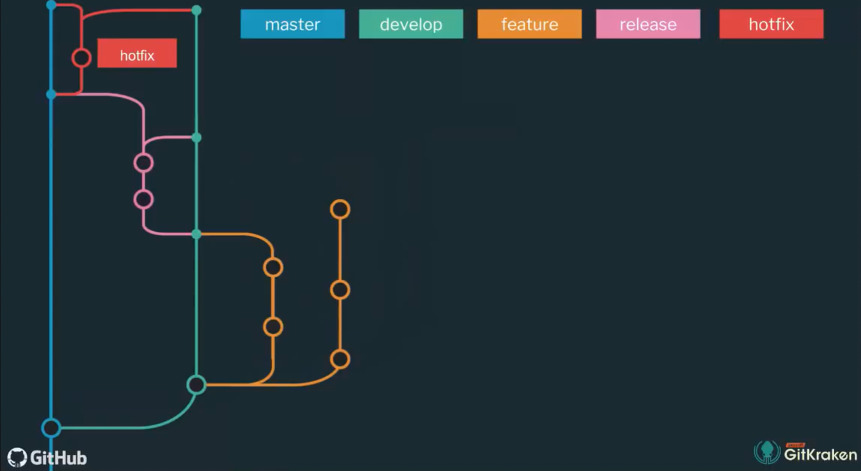

git gcBranching Strategies

Agree on a Branching Workflow in your team:

GIT allows you to create branches but it doesn't tell you how to use them

you need a written best practice of how work is ideally structure in your team - to avoid mistakes and collisions

it is highly depends on your team / team size on your project and how you handle releases -it helps to onboard new team members ("this is how we work here")

Integrating changes and structuring releases:

mainline development ("Always Be Integrating"):

- few branches

- relatively small commits

- high quality testing and QA standards

Stale, release and feature branches:

- different types of branches

- fulfil different types of jobs

GIT Flow vs Trunk based dev:

GitHub Flow: very simple, very lean:

- only one long-running branch ("main") + feature branches

GitFlow: more structure, more rules,

- long-running branches: "main", "development"

- short-lived branches: "features", "releases", "hotfixes"

Branch Name Create from Merge back into develop master - feature develop develop release develop master and develop hotfix master or develop master and develop

Tagging

Tag allows you to capture a reference point in your project history, such as release versions

Tags allow making points in history as important

A named reference to a commit

An annotated tag (most common) contains additional information such as name, message, and email of the person who created the tag

A lightweight tag points to just a commit hash

Create a tag (lightweight):

bash# add lightweight tag git tag [tag name] # create a tag for older commit git tag [tag name] [commitSHA]Annotated tags:

bashgit tag -a [tag name] -m [message] [commitSHA]List tags:

bash# list tags git tag git tag --list git tag -l # list tags with annotations git tag -l -n git tag -l -n [number of lines from the annotation] # filter tags # list tags beginning with "v2" git tag -l "v2*"Push tags to remote repository:

bashgit push origin [tag name] # push all tags git push origin --tags git push --tagsgit fetchautomatically retrieves shared tagsTo delete the tag:

bashgit tag -d or --delete [tag name] # delete remote tags like remote branches git push origin :[tag name] git push origin --delete [tag name] git push origin -d [tag name]

Checking Out Tags

- Tags are not branches

- Tags can be checked out, just like any commit

git checkout -b [new_branch] [tag name]git checkout [tag name]: same as checking a commit

Git Submodule

It often happens that while working on one project, you need to use another project from within it. Git addresses this issue using submodules

Submodules allow you to keep a Git repository as a subdirectory of another Git repository. This lets you clone another repository into your project and keep your commits separate

git submodule add [url of repo]

# view status (working, staging, or indexed files) of all the submodules

git submodule status

# updates submodules after switching branches

git submodule update

# after cloning a new repo, if you need to add submodules to it from .gitmodules file, use this command

git submodule update --init

# if the submodules inside a newly cloned repo are nested, then use this

git submodule update --init --recursive

# pulls all changes in the submodules

git submodule update --remoteA .gitmodules file is created when we add a submodule to the project. This is a configuration file that stores the mapping between the project's URL and the local subdirectory you've pulled it into:

[submodule "DbConnector"]

path = DbConnector

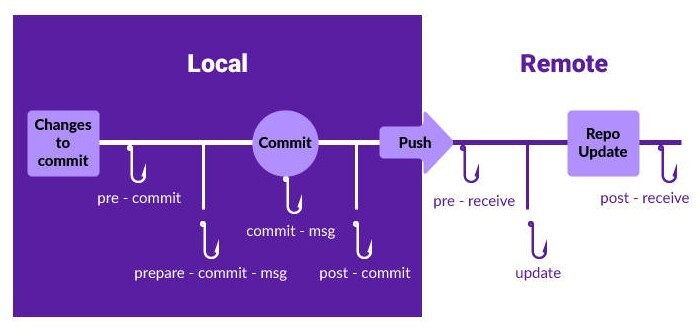

url = https://github.com/chaconinc/DbConnectorGit Hooks

Git Hooks are shell scripts that get triggered when we perform a specific action in Git

- Git hooks reside in the

[project-dir]/.git/hooks/directory - There are around 28 hooks

Based on the git operation, any one of the following git hooks will be triggered

Client-side:

Committing workflow hooks:

pre-commitprepare-commit-msgcommit-msgpost-commit

Rewriting:

pre-rebasepost-rewrite

Merging:

post-mergepre-merge-commit

Switching/Pushing:

post-checkoutreference-transactionpre-push

Email workflow hooks:

applypatch-msgpre-applypatchpost-applypatch

Server-side:

updatepre-receivepost-receive

- Hooks are simple text files

- Hooks can be written in any scripting language like python, Ruby, and so on

- The script filename should match the hooks' name. For

post-commithook the script filename should bepost-commit

List of other hooks:

proc-receivepost-updatepush-to-checkoutpre-auto-gcsendemail-validatefsmonitor-watchmanp4-changelistp4-prepare-changelistp4-post-chanagelistp4-pre-submitpost-index-change

Git Maintenance

It essentially provides a way to add cron-jobs that run daily, hourly and weekly maintenance tasks on your Git repositories

You can turn it on for your Git repository by simply running:

git maintenance startThis will modify your .git/config file to add a maintenance.strategy value set to incremental which is a shorthand for the following values:

gc: disabledcommit-graph: hourlyprefetch: hourlyloose-objects: dailyincremental-repack: daily

This means that every hour it will rebuild your commit graph and do a prefetch, and once per day it will clean up loose objects and put them in pack-files and also repack the object directory using the multi-pack-index feature (read more about that in an incredible blog post from GitHub's Taylor Blau here)

- This makes things like

git log --graphorgit branch --containsmuch, much faster

File system monitor:

- it could detect when virtual file contents were being requested and fetch them from a central server if needed

git config core.untrackedcache true

git config core.fsmonitor trueSigning

Signing commits with SSH

# use SSH for signing

git config gpg.format ssh

# path to your public keys

git config user.signingKey ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub

# try to sign commit with your keys

git commit -S

# sign the ref update on the server and

#have the server save a transparency log with verifiable signatures somewhere

git push --signedOther Git Commands

# show results in columns

seq 1 24 | git column --mode=column --paddin=5Worktrees

Working on more than one branch at a time

- Provide a new working directory for each branch

git worktree add -b bugfix ../project-branches/bugfix

cd ../project-branches/bugfixScalar

Git now (since Oct 2022, Git 2.38) ships with an alternative command line invocation that wraps some of this stuff. Useful for huge projects

scalar

# usage: scalar [-C <directory>] [-c <key>=<value>] <command> [<options>]

#

# Commands:

# clone

# list

# register

# unregister

# run

# reconfigure

# delete

# help

# version

# diagnoseScalar is mostly just used to clone with the correct defaults and config settings (blobless clone, no checkout by default, setting up maintenance properly, etc)

If you are managing large repositories, cloning with this negates the need to run

git maintenance startand send the--no-checkoutcommand and remember--filter=tree:0and whatnot

Running scalar clone [repo https url/ssh link] will do the following:

- prefetching

- commit-graph

- filesystem monitor

- partial cloning

- sparse checkout

Git Large File Storage

An open source Git extension for versioning large files

Git Large File Storage (LFS) replaces large files such as audio samples, videos, datasets, and graphics with text pointers inside Git, while storing the file contents on a remote server like GitHub.com or GitHub Enterprise

# install LFS

git lfs install

# select the file types you'd like Git LFS to manage

git lfs track "*.psd"

# make sure .gitattributes is tracked

git add .gitattributes

# now proceed with commit

git add file.psd

git commit -m "Add design file"

git push origin masterSmudge and Clean

Git RCS keywords: $Date$

Github Folder

The below mentioned files can be created in the .github folder:

CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md: Defines standards for how to engage in a communityCONTRIBUTING.md: Communicates how people should contribute to your project. (making pull request, setting development environment...)FUNDING.yml: Displays a sponsor button in your repository to increase the visibility of funding options for your open source projectISSUE_TEMPLATE: Folder that contains a templates of possible issues user can use to open issue (such as if issue is related to documentation, if it's a bug, if user wants new feature etc)config.yml: Customize the issue template chooser that people see when creating a new issue in your repository by adding aconfig.ymlfile to the .github/ISSUE_TEMPLATEfolder

PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATE.md: How to make a pull request to projectstale.yml: Probot configuration to close stale issues. There are many other apps on Github Marketplace that place their configurations inside .github folder because they are related to GitHub specificallySECURITY.md: Gives instructions for how to report a security vulnerability in your projectSUPPORT.md: Lets people know about ways to get help with your project. For more informationworkflows: Configuration folder containing yaml files for GitHub ActionsCODEOWNERS: Pull request reviewer rules. More info heredependabot.yml: Configuration options for dependency updates. More info here